“BATTLE OF THE TITANS”

by

Michael Keyser

After racing actively in the IMSA Camel GT series throughout the 70s and into the 80s, I’d been away from the sport for the better part of fourteen years. As a member of the Road Racing Drivers Club (RRDC), I received some correspondence in the fall of 1994 from Brian Redman, who was serving as president. In 1972 Brian had kindly allowed us to film him at his home in England for the documentary, THE SPEED MERCHANTS. Unsure if he’d ever actually seen the film, I sent a copy of the video to him. A short time later I received a thank you letter back. Seeing the name of my company, Worldwide Marketing Associates, Brian asked if I would be interested in helping him market his vintage motor race, the JEFFERSON 500. One thing led to another, and I ended up helping him produce the race program for the 1995 event.

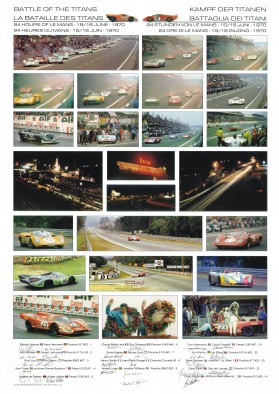

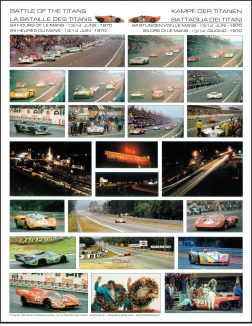

We collaborated on an “inside” story about Porsche’s first outright win at the 1970 24 Hours of Le Mans, called BATTLE OF THE TITANS. The race, and the celebration of Porsche’s win, was the focus of last year’s JEFFERSON 500, and we used some of the photographs I’d taken at the race to accompany the story. We also used some of my photographs in the program for a trivia contest. I sudenly realizing that vintage racing had become very popular and reasoned there might be a market for photo-nostalgia from the early 70s, of which I had quite a bit. During the next few months I put together a catalog of photographs that had originally been used for a photo-essay I’d written in 1973, also entitled THE SPEED MERCHANTS. Having completed the catalog, I set out to produce a limited edition lithograph commemorating Porsche’s victory at the 1970 24 Hours of Le Mans. As work progressed, I decided to try and locate as many of the drivers who had finished the race (or driven top Porsches), as I could and have them sign the print.

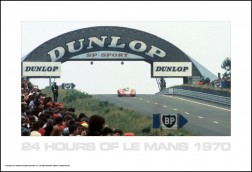

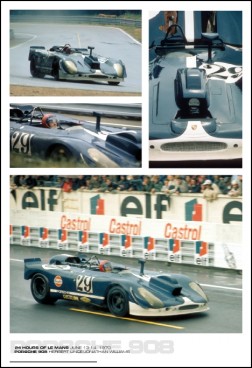

I’d taken the 24 photographs that were to eventually make up the BATTLE OF THE TITANS lithograph on June 15 and 16, 1970 at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. All were shot on transparency color film, using either a Nikon-F (35mm), a Hassleblad 500 EL (2 1/4″ x 2 1/4″) or a Speed Graflex (4″ x 5″). For over 25 years they had remained in loose leaf binders, inside a box or on one of my bookshelves. In the fall of 1995, I scanned the images to CD-Rom disks, refined them using Adobe Photoshop and during a two month period designed the print as a collage. During this time I’d also managed to locate 25 of the drivers, all of whom agreed to sign 500 of the prints. Finding them was one thing. Actually obtaining their signatures was quite another.

One thousand and twenty-five of the lithographs were printed by The Art Litho Company of Baltimore, Maryland in a 27″ x 39″ format, and on the morning of December 11, the prints were transported by truck from the company to my home in Butler, Maryland. On the afternoon of the same day, I packed 525 of the virgin prints into two wooden cases (260 per case) and blasted off for Dulles Airport.

Two weeks before I’d called KLM and explained I’d be traveling with two very large, oversize cases, each weighing approximately 130 pounds, on one of their Dulles/Amsterdam flights. The voice on the phone told me I’d have to pay a substantial amount of overweight, but that the cases could be shipping as hold luggage. When I arrived at Dulles, I found that Northwest had been subcontracted to fly for KLM and they refused to allow the cases to be checked as luggage. They’d have to be shipped the next day as air freight, I was informed. I knew this wouldn’t work, as I was scheduled to leave from Amsterdam the following afternoon for Frankfurt.

Intermittent pleading and threatening did no good, so as the time of departure approached, I figured I’d be better off taking some of the prints than none. After all, I’d spent the better part of the past three months contacting 20 of the drivers who lived in Europe and arranging to meet with them so they could sign the prints. If I didn’t show up, not only would it be embarrassing, but the whole project was in jeopardy. So I opened one of the cases, dragged out a large handful of prints, closed the case and threw it on the scale. Fifty-five pounds qualified it as hold luggage. Before sprinting to the departure gate, I handed a card to one of the Northwest agents and asked that she call my wife, Beth, and explain what had happened. The bottom line: one of the cases and a large number of prints were still at the airport.

Once inside the plane I was surprised to be directed toward the front and into business class. I hadn’t checked my ticket closely and just assumed I’d be in economy. I cursed my travel agent for the additional cost, and at the same time blessed him for the added comfort I could look forward to. As one of the flight attendants showed me to my seat, I told her what I’d just been through. “Don’t worry,” she said, winking. “I’m going to take good care of you.” This she did, all the way across the Atlantic, starting with a stiff vodka and grapefruit juice. Thank you Lynn McDaniel!

The flight was uneventful, and the following morning when I landed at Amsterdam’s Schipol Airport I was extremely relieved to see the yellow case arrive in the baggage claim area. In the previous few years I hadn’t driven much but my faithful 1986 Honda CRX, so when I slid into the rental car I felt as if I were at the wheel of a space ship. I spent most of the 45 minutes driving south to the little town of Blaricum, where Gijs van Lennep lived, trying to figure out how to turn off the windshield wipers. Gijs had faxed me a map and directions which I suspected were overly simplistic. “Take the LAREN – BLARICUM – HUIZEN exit off highway A-1, drive 3 kilometers to Blaricum and turn right. My house is halfway up the hill”. For more than an hour, feeling like a total fool, I fumbled my way through narrow Dutch streets that wound hither and yon, asking anyone I came across if they knew where Gijs van Lennep lived…then did an imitation of a race driver. All I got for my efforts were shakes of the head and blank stares. I finally came on a young store-owner who knew who Gijs was and he gave me precise directions. Living in the Netherlands where the land is flat as a pancake, Gij’s idea of a hill and mine differed markedly. I found his house in a wooded neighborhood just off what was no more than a slight incline.

I pulled up outside at around 11:00 A.M. and was greeted by Gijs, looking very dapper in a hounds tooth jacket and silk cravat. After wheeling the case into his dining room on the small luggage cart I’d brought, I found the threads on the two locking screws had been badly buggered (courtesy of Northwest) and two sets of pliers were required to remove them. On the flight over I’d subtracted the weight of the wooden case (31 lbs.) from the weight I’d seen on the scale (55 lbs.) and came up with a weight for the prints (24 lbs). I knew each one weighed almost half a pound, so in the rush at Dulles I suspected, in my haste, I’d probably only left 50 in the case when I’d pulled out a “handful”. Sure enough, I found 53 inside. It didn’t take Gijs long to sign his name 53 times, but it was a leisurely affair – our conversation drifting from the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1970 where he’d driven a Porsche 917 with David Piper, to the 1971 race which he’d won with Helmut Marko, to his main vocation now which was conducting driver’s schools throughout the Netherlands.

When he finished, I phoned my office in Baltimore and arranged for an additional 150 prints to be shipped to Sindelfingen, Germany, the small town outside Stuttgart where Hans Herrmann lived. It would be four days before I was due to arrive there, so I figured UPS could make delivery by then. Three hours after arriving, having been fed a sandwich and some Dutch cheese by Gijs, I said goodbye and headed back to Schiphol Airport. There was no problem checking the case as luggage, and at 6:55 I caught a flight to Frankfurt, Germany.

I’d originally planned on driving to Cologne that evening and meeting up with Erwin Kremer the following morning, but the frantic activity of the previous 24 hours had caught up with me. After renting an Opel station wagon, I made for the Frankfurt Airport Sheraton which was a 12-story Bauhaus bunker visible from the terminal. Parking in the basement of the structure, it took me a good half hour of trundling the case and my luggage through the bowels of the building before I found the hotel lobby. For a stiff DM 749 ($576) I was assigned a place to sleep and fed a club sandwich. The next morning I was up at 7 A.M., and after a $26 breakfast, blasted up the autobahn toward Cologne as fast as the Opel would carry me.

The workshops of Erwin and Manfred Kremer, better known as Porsche-Kremer, were on the outskirts of the city, and in a phone call en-route their highly efficient manager, Achim Stroth, gave me directions. I hadn’t laid eyes on Erwin for over 20 years, but on pulling into the parking lot, recognized him immediately as the person standing outside the two-story office and showroom, behind which was the workshop.

Erwin explained that he was quite busy as he was due to leave for vacation the following day, but would sign the prints when he had a moment. He led me up to the modern suite of offices above the showroom where I met Herr Stroth and renewed an old acquaintance with brother Manfred. In 1974 I’d rented a “special” 3-liter Porsche-Kremer motor for the final race of the IMSA season in hopes of propelling Milt Minter, in a Toad Hall Porsche, past Peter Gregg for the series championship. Manfred had flown over with the motor for the final race of the 1974 IMSA season that was traditionally held at Daytona during the Thanksgiving weekend. Unfortunately the motor swallowed a valve while Milt was in the lead and Peter had gone on to capture the IMSA title.

At the workshop that morning was Evangelia Kamari from MSK International Transport, the company that handles the shipping of Porsche-Kremer’s race cars, parts and pieces around the world. After being introduced to her, I immediately explained my predicament with the prints. She agreed to shepherd those being sent from my office in Baltimore through customs to Hans Herrmann’s office in Sindelfingen, and also coordinate the shipping of the balance that would eventually have to be sent around to all the drivers at a later date to be signed.

Erwin was indeed busy as a bee tending to last minute business before his vacation, which included a pow-wow with Seppi and Roy Korytko, two American-born German brothers who’d been handling the fiberglass work on Porsche-Kremer’s race cars for a number of years. While he met with them, Erwin gave me free run of the offices, showroom and workshop. I took full advantage of his hospitality, and armed with my camera I quickly pumped four rolls of film through it.

The 1995 Daytona 24 Hour-winning Kremer Porsche was on display in the showroom and I shot the two Kremer brothers with the two Korytko brothers and the Porsche-Kremer body man as they masked off its side panels with tape and discussed modifications for a proposed entry at Le Mans that coming June. To commemorate 24 consecutive years of competition at Le Mans, Porsche-Kremer had produced a very slick 4-color brochure, a copy of which Herr Stroth gave me, along with calenders, posters and other memorabilia. Erwin finally broke away from business long enough to sign the prints, and late that afternoon I packed up and headed back to the Frankfurt Airport.

I thought I knew where I was going (after all I’d driven up to Cologne just that morning), but I managed to overshoot a turnoff on the autobahn and suddenly found myself heading west toward Aachen when I should have been motoring south to Frankfurt. Trying to cut across country and get back on track, I added forty-five minutes to my journey. To make matters worse, I missed the exit for the airport and wasted another twenty minutes getting turned around. By the time I’d dropped off the rental car and arrived where I was supposed to check in, the flight to Graz, Austria had departed. The penalty for having gone astray was being sentenced to another deutchmark-draining night at the Sheraton. Adding insult to injury, the first flight to Graz the following morning was full. After putting my name on the waiting list, I wheeled the case of prints and my luggage through the airport, across the pedestrian bridge and into the lobby of the Sheraton once again.

Luck was with me the next morning, and I managed to secure the very last seat on the Tyrolean Airlines Frankfurt-Graz flight which had flight attendants decked out in leiderhosen and knee stockings. Once in the air I struck up a conversation with the fellow sitting next to me who was a chemist for Shell Oil traveling to Hungary to give a dissertation on lubricants. After a bumpy hour and a half, we descended toward Graz and into a raging snowstorm. The pilot pulled up at the last minute on the first landing attempt and we circled blindly for half an hour while the runways were cleared. “If he does that again, tell him to let me have a go,” I joked nervously with the stewardess. Our next try was successful, and we swooped down to a snow-covered Austrian countryside. The yellow case had made it once again, and I quickly grabbed a cab into the city.

Had I not missed my flight the previous evening, I’d have spent the night in Graz at the Schlosberg Hotel, which was owned by Dr. (of law) Helmut Marko, the Austrian driver I was coming to see. Although I’d faxed Helmut from Frankfurt explaining that I’d (hopefully) be arriving around mid-morning, because of the delay caused by the snowstorm I was badly behind schedule. My flight to Stuttgart (via Vienna) left at 3:40 that afternoon, and it was already high noon. My cab driver was a fan of American country/western music and as we set off he popped a Johnny Cash cassette into his tape player. The snow had turned to slush on the roads, and as this Austrian Garth Brooks wanna-be drove at an excruciatingly slow 20 kilometers an hour toward the city he regaled me in broken English with stories of his yearly trips to Pensacola, Florida where he had a relative.

Helmut was pacing the lobby of the hotel when I arrived, and after apologizing for keeping him waiting he ushered me into a tastefully appointed meeting room. Like Erwin Kremer, he was quite busy, in his case overseeing renovations to the hotel that had to be completed in time for his Christmas party the following evening. He would sign ten or fifteen prints then rush off to make sure the workmen were following instructions properly, but within an hour he’d finished the job. After meeting his wife, Imi, I set off for a quick walk around Graz.

From the outset, I wanted to tape any conversations I had with the drivers while they were signing the prints, and to that end I’d brought a small recorder with me. On arriving at Gijs van Lennep’s I found the Olympus tapes I’d bought wouldn’t fit my Norelco recorder. There wasn’t time for conversation with Erwin at Porsche-Kremer, besides which his English was fairly limited, but that morning at a duty-free shop in the Frankfurt airport I’d bought a new recorder. No more than a minute after making the purchase, while paying $3 for a copy of USA-TODAY, I’d set down my new $60 recorder to make change, and some bast–d had swiped it!! So I set out to find an electronics store in Graz and buy another.

The snow had stopped and the city was truly a winter wonderland, alive with the spirit of Christmas. A five minute walk brought me to the main square where I found an Austrian equivalent of Macy’s. I made a quick purchase, then considered grabbing a bite to eat. I’d given my wallet a break at the Sheraton that morning, so breakfast had been limited to a meager snack on the airplane. But checking my watch I saw it was almost 2 o’clock, and not wanting to miss another flight I decided I’d better get back to the hotel, grab the prints and make for the airport. The concierge at the hotel called me a cab, and when it pulled up outside I couldn’t believe my luck. Of all the cab drivers in Graz, I’d drawn the same Austrian hillbilly who’d brought me in that morning! On the return trip, again at 20 kilometers an hour, I was serenaded by Conway Twitty.

Checking in, I found my flight to Stuttgart (by way of Vienna) had been canceled due to bad weather in the capitol. Now what!?, I thought. I was due to meet Hans Herrmann, Herbert Linge and Kurt Ahrens in Sindelfingen the next morning at 9 A.M. My dismay did a quick one-eighty when I discovered there was a flight leaving for Zurich twenty minutes later and a connection would still get me to Stuttgart that evening. Not only that, seats were available.

It was raw and raining when I landed in Stuttgart. The yellow case appeared, I rented a car and drove for half an hour to Sindelfingen. Although I’d made a reservation the previous evening at the Best Western, I decided to opt for a Ramada Hotel just off the autobahn. After once again dragging the yellow case and my luggage upstairs I called room service, gobbled down a sandwich and collapsed.

The next morning I set out for Hans Herrmann’s office. At the front desk I asked the concierge if he could show me on a map how to get to Karl-Orffstrasse. This slightly simpering fellow gave me a quizzical look, scratched his head then walked outside to consult with a cab driver. Better yet, I thought, why not have the cab driver lead me there. He agreed to this, so I descended to the garage beneath the hotel where I’d parked the previous evening. On entering, I’d been issued a ticket by an automated machine, but no matter which way I shoved it into the slot, the barrier refused to budge. I stomped back up to the front desk and asked the concierge if there was some trick. Do you have to say “open sesame” in German, I wondered. Looking at the ticket, he pouted “It must be walidated, of course.” How was I supposed to know, I asked. Nobody had explained the procedure to me when I’d checked in. “Well! Everybody knows,” he told me, fluttering his eyes. “No”, I shot back. “Everybody doesn’t know! I’m part of everybody, and I don’t know!” Even after the ticket was walidated, I still couldn’t get the barrier to lift, so having run out of patience, I nudged it aside with the nose of the car and sped up to the street where the cab driver was still waiting patiently, the meter undoubtedly having been running the whole time.

Hans Herrmann Auto-Tecknik occupied the ground floor of a small, modern three-story office building, and on arriving I found Hans, Herbert Linge and Kurt Ahrens waiting in the boss’s very posh, Persian-rug-appointed office. Also on hand were Kurt’s son, and Eberhard Strahle, a German photo/journalist Vic Elford had introduced me to by phone. Eberhard had been instrumental in helping me track down Herr Ahrens. Looking around the office I saw there was a large wooden desk to one side that was perfect for the job at hand. I was also delighted to see the 150 prints that had been shipped from Maryland had arrived. This would be the first multiple signing, so it took a minute to figure out who should go first, based on the location of their name on the print, so the ink wouldn’t get smudged.

Once the order had been decided, I fired up my new recorder and the three Porsche-meisters set to work with Teutonic presicion and much conversation. It was all in German, but the word neunhundertsiebsener kept cropping up, referring to the fabled 917. Hans Herrmann, who was first in line, was far and away the quickest, cupping his hand and stacking the prints on top while they waited for Herbert Linge. When I pointed this out, he noted that Linge and Ahrens were retired, but he still had a business to run. The chore was accomplished in a little over two hours, after which Herbert Linge led me through the streets of Sindelfingen and back to the Ramada Hotel.

At this point in the trip I was scheduled to fly to Nice to meet up with Guy Chasseuil, but after making contact with him in mid-November through Vic Elford (who speaks fluent French), I’d been unable to reach him again to make definite arrangements. After four days on the road, I was ready for a breather. Besides a one-day layover in Stuttgart would allow me to visit with Jürgen Barth, an old friend who I hadn’t seen since 1978. In 1972, he and I had co-driven together at Sebring, the Targa Florio, the Nürburgring and Le Mans in my 2.5 911. Jurgen had worked for Porsche then when we were both in our twenties, and now he was in charge of Porsche’s Customer Racing Department which was headquartered in Weissach. Jürgen is also one of the three driving forces behind the FIA-sanctioned BPR Global Endurance series which is three years old and growing. I’d called him before leaving the U.S. and had touched base while traveling, so on returning to the hotel I called him and he gave me directions to the legendary test facility.

While waiting for Jürgen in the reception area at Weissach I told the lady behind the desk that I hadn’t seen him for some time and asked if he’d changed any. “Oh, no,” she said. “He’s just as elegant as ever.” Which I found to be the case. Driving a new Porsche (what else), Jürgen zipped me off to his office which was directly adjacent to the test track. While he tended to some business, I checked in with my office and called several of the drivers to confirm that our meetings were still on for the upcoming days. Before leaving Weissach, Jürgen invited me for lunch the following day at the home of his mother, who I’d met briefly back in 1972 and remembered as being delightful.

On my return to the Ramada Hotel, I discovered that a German company’s Christmas party was in full swing. I took a shower and descended to the bar where an affable Jamaican fellow named Lewis Williams was in command. He told me that the company having the party, CUT Design GmbH, manufactured stickers and decals. By this time the sticker-meisters had finished their cocktail hour, which had been held in the spacious lobby, and moved to the ballroom for the main feast, leaving behind ravaged tables of hors d’oeuvres like so many spoils of war.

After dinner some of the party-goers, dressed to the nines in tuxedos and evening dress, filtered back to the bar in varying states of inebriation. Before long I was swept up in the celebration and dragged back to the ballroom to examine a van on display that was plastered with examples of their stickers and decals. When one of the women discovered I was an American, she quickly scribbled her address down and made me promise I’d send her some of the “miracle drug” Melatonin, which had just been banned in Germany. It was well after two o’clock before I slid between the sheets.

The next day I drove out to the little town of Bietigheim and had a delicious lunch with Frau Barth and Jürgen. Afterwards Jürgen had to rush off to the airport to pick up two of the promoters from the track at Anderstoorp, Sweden, who had flown down to discuss their 1996 BPR race. While he was gone, I had a long conversation with Mrs. Barth, which was quite amusing since I spoke no German and she no English. On Jürgen’s return, I met the two Swedish promoters, then Jürgen pulled out his father’s scrapbook which had page after page of fantastic photographs from the 50’s when Edgar was Porsche’s “golden boy” of racing. After tea and strudel, baked by Frau Barth, I took off for the Stuttgart Airport to catch my flight to Zurich.

On arriving at Kloten airport, I rented a car and set out for the town of Bludenz, 75 miles away in the Austrian alps, where I was scheduled to meet Rudi Linz the following morning. The Schloss Hotel in Bludenz, where I arrived around 9 P.M., was an overgrown chalet of carved wood and heavy stone construction, with a grisled German shepherd whose idea of guarding the fort was stretching out like a bear rug smack in the middle of the lobby.

I slept well, and the next morning woke to brilliant sunshine and a dramatic backdrop of snowcovered peaks outside my window. I called Rudi Linz at 8:30, and half an hour later he appeared at the front desk. We’d never met, but I had an idea what he looked like from photographs I’d taken of him during the early 70s. Of course 25 years had passed, and the distinguished gentlemen who greeted me didn’t quite match the picture I had of him. I followed Rudi through Bludenz to his Porsche/Audi/VW dealership, where he gave me a quick tour, then on to his home which was a very attractive semi-modern affair that sat in the middle of a snow-covered field.

By now I’d become quite adept at wrestled the heavy yellow case out of rental cars, and in short order I was inside and Rudi was scribbling away. His wife, and teenage son and daughter popped in and out as he worked his way through the 200 prints, after which I snapped an informal family portrait. Frau Lins and the kids were headed to a Christmas bazaar, so I followed Rudi back to the hotel where he treated me to a delicious lunch and some stories of his racing career. I had a 6:45 flight to Frankfurt, and a connection to Luxembourg where I was to meet Nicolas Koob, Erwin Kremer’s co-driver. I wasn’t returning to Zurich, but instead leaving from Friedrichshafen, which was northwest of Bludenz, just across the German border.

I made the trip in two hours and zeroed in on the airport with no problem. On entering the terminal I was surprised to find there was no Alamo office to be seen. My flight was due to leave in twenty minutes, so I had no choice but to hand the keys and rental contract to the Lufthansa personnel and tell them I’d call Alamo from Frankfurt and let them know where to find their car. I was in Frankfurt within an hour, where I barely had time to make the call before catching the Luxair flight to Luxembourg.

I arrived in a soupy fog and steady drizzle, but my spirits were lifted considerably on meeting Nicolas Koob, a stocky, jovial bear of a man in his mid-50s. He’d generously offered to pick me up and was accompanied by his friend Piter Sinner who worked for Luxembourg TV-9. I’d already learned from Jürgen that Nicolas was quite a legend in Luxembourg where he operates a bus company. Among other things, he organizes a yearly trip to the Monte Carlo rally in which he’d competed a number of times. The yellow case just did squeeze into his BMW, and I was spirited away to the very fancy Parc Hotel. After depositing my goods in the room, I joined Nicolas, Piter, and several of their lady friends for a drink in the bar. After some spirited conversation, we agreed to meet the following morning at 10 A.M. so Nicolas could sign the prints. The Parc Hotel boasted a sprawling lobby, and there was no problem commandeering a corner in which to set up for the signing. Nicolas had alerted several members of the local press about the event, and I had sales brochures, magazine advertisements, photographic catalogs, etc., (as well as a press release I’d composed on the hotel computer late the previous evening) laid out when he and a small entourage arrived. There were several newspaper reporters and photographers in the group, as well as Pascal Feller, a representative from Porsche-Luxembourg.

After the signing “ceremony”, we moved to the hotel restaurant where I choked down yet another gourmet meal. Several more photographers arrived while we were eating, requiring Nicolas to put down his knife and fork and play-act the signing of a print. It was still raining and foggy when I left in a cab for the airport with not-as-much-time-as-I’d-have-liked to catch my 4:55 Sabena flight to Belgium.

When I arrived in the baggage claim area of the Brussels airport, I was immediately set on by a seedy looking fellow asking if I needed a taxi. I indicated I did, but it was not until I exited the terminal and saw his bedraggled Volvo (lacking a dome light) that I realized I was in the clutches of a gypsy driver. A Hungarian one at that. Although he spoke little English, he immediately informed me he had a bad cold, a wife and three children and that I should sponsor them so they could immigrate to America. I’d called the Mövenpick Hotel from the airport and booked a room. On arrival forty-five minutes later, after battling through rush hour traffic, the fare I was quoted by Mr. Hungary sounded more like the down payment for his family’s impending trip to America. I asked the hotel concierge what the going rate was (half of what I was being asked to pay), and the driver meekly accepted it without complaint.

Early the next morning I took a taxi to Hughes de Fierlant’s office where I found him waiting and ready to sign. During our conversation, he asked why I was flying all over the place when the distances between the cities I had to visit was not all that great. While this was true in some cases, in others, travel by car would have been impossible if I hoped to accomplish the job in eleven days. My next destination was Paris – only three hours away by car – and since Hughes finished signing quickly and was due at a business luncheon, there was no reason for me to stick around. If I rented a car and drove, I could be in Paris by the time I was scheduled to take off from Brussels.

Hughes told me there were several rental agencies nearby and offered to drive me around to see if I could find a car. I soon discovered there were none to be had in all of Brussels due to a one-day wildcat strike by Sabena personnel. After coming up dry at four locations, we returned to his office and I grabbed a real cab back to the airport.

By now I’d grown accustomed to looks of horror on the faces of the airline agents when I lifted the case with the prints onto the scales and it registered 113 pounds. “You know you must pay overweight!!” they would inform me. Each time I calmly acknowledge that fact and forked over the dough. The airport was a seething caldron of irrate humanity because of the Sabena strike, and even though I was flying Air France, in an act of sympathy with their brethren no baggage handlers were working. This meant dragging the yellow case and my baggage all the way out to the gate, with a stop along the way for a protracted shakedown by airport security. I’d worked up a healthy sweat by the time I finally arrived, which wasn’t helped by the banks of radiators lining the walls that were going full blast.

It was an up and down flight to Paris, and on arriving I rented a car and headed into the city. It was 5:30 and once again I found myself in the middle of rush hour, surrounded by Frenchmen whose nerves and tempers had been severely frayed for the past month during disruptive municipal strikes. Thankfully, the workers had reached a temporary accord two days before. After being swept around the peripherique (beltway) surrounding Paris, I arrived at the very elegant Hotel Lutetia which was well positioned in the center of the city on the Blvd. Raspail.

A reservation had been made there for me by Jean Pierre Avice, an old friend from Le Mans who owns Twin Cam Associates, a film production company headquartered in Paris. Jean Pierre had worked on numerous motion pictures shot in France (including many of the Pink Panther series), and I was shown to a room fit for a movie star. Opening my window, I had a spectacular view of the Invalides and the Eifel Tower beyond, which was lit up like a Christmas tree. Thankfully, Jean Pierre had negotiated a discount rate for me. I’d arranged to meet Claude Ballot-Lena and Gerard Larrousse at the hotel the following morning, but it was still early, so after putting my feet up for a bit, I took a drive around Paris, which was living up to its name, the City of Lights, during this holiday season.

The next morning Claude arrived first, having driven in from his home in the Paris suburb of Garches on his motorbike. We waited half an hour for Gerard to show, during which time Claude explained that he now operates an industrial cleaning business as well as a restaurant called Chez Henri in the seaside town of Deauville. We weren’t able to raise Gerard on his “mobile”, so Claude set to signing the 200 prints alone. No sooner had he finished, than Gerard arrived and we went through the whole procedure again.

The next driver in my sights was Englishman, Jonathan Williams, who with Herbert Linge had co-driven the Porsche 908 that was used as the camera car in the 1970 race for Steve McQueens film LE MANS. My destination was the small town of Hendaye, which was located on the Atlantic coast smack on the French/Spanish border. Although I’d planned to fly from Paris to Biarritz, then rent a car and drive to Hendaye, a short distance away, I decided to put the bit between my teeth and drive. Although it was quite a distance (500 miles), I consoled myself in the fact that I’d be able to save some money by refunding the unused air ticket and also avoid an overweight charge. It would also allow me to stop off in Le Mans and visit briefly with Jean Pierre Avice who I hadn’t seen since 1978.

Although Gerard Larrousse assured me it was quite simple to get out of the city and onto the autoroute to Le Mans, after traveling no more than three blocks from the hotel, I found the gendarmes had the whole area cordoned off. Perhaps a post-strike tremor. Every time I turned a corner I either found a one-way street going the wrong way or a gendarme directing me back where I’d just come from. In frustration, I finally made for the Seine. After working my way along the river to the southern outskirts of Paris, I was back on the peripherique. I managed to get on an autoroute alright, but found myself headed DIRECTION-ROUEN, rather than DIRECTION–CHARTRES. I doubled back through Versailles, finally got on the right road and arrived in Le Mans around 6:30.

I followed Jean Pierre’s directions to the small town outside Le Mans where he was in the process of renovating the family’s country house. After spending several very pleasant hours with him having a drink or two and some of the local fois gras, I followed him back to Le Mans where he pointed me south in the general direction of Tours. As it turned out, the road on which he unleashed me was none other than the Mulsanne Straight. It was dark and rainy, and the track had changed quite a bit, having sprouted numerous round-abouts that doubled as chicanes, but as I progressed along, it all became familiar. Reaching the end, I passed through the little village of Mulsanne, then put my head down and began to drive.

The farther south I progressed, the thicker the fog became, until I was navigating largely by following the white line down the center of the autoroute. There was very little traffic, mostly trucks, which allowed me to keep my foot firmly planted to the floor of my rental Renault, which topped out at 140 kilometers. I reached the outskirts of Bordeaux around 1:30 A.M., and could go no further. Still 130 miles from Hendaye, I at least felt I was within striking distance, and after searching longer than I would have liked at that hour of the morning, I found what appeared to be a small motel. On closer examination, I began to wonder.

When I pulled up outside the Hotel Premiere Class, I found the driveway blocked by a wrought iron gate. I parked, climbed out of the car, and as I approached the gate, a light on a pole nearby suddenly came on. How considerate, I thought, figuring someone inside had seen me. I pushed open a metal door off to one side, walked up to the building, then circled it, but could find neither a lobby or a human being. It was all a little spooky. There were three floors with connecting stairways and catwalks. The sign said it was a hotel, but I found it a bit strange that there was no place to check in.

After my second circuit I discovered an alcove, inside of which was a close relation to an ATM machine. There was a slot to insert a credit card, so with some apprehension, I offered mine and it gobbled it up. There was a whir of gears then a menu popped up on the screen (all in French). I have a very poor command of the language, but I was able to figure out what I was being asked. Did I want a single room for 149 Francs? How many people were in my party? How long would I be staying? Did I want a “petit dejeuner” at the nearby Cote de Cote restaurant for an additional 21 francs? I pushed the appropriate buttons, and in a few moments I heard the sound of a printer activating, after which the machine spat out a receipt, followed (thankfully) by my credit card. At the bottom of the receipt was a room number and what I presumed was an entry code. I retrieved my bag from the car, proceeded to the room and punched in the code on a keypad. Magically, the door opened. Although the entire unit was of modular fiberglass construction, including the bathroom, the bed was comfortable and I was asleep in short order.

I’d figured out how to set the alarm clock before passing out, which jarred me awake four hours later at 6 A.M. The Cote de Cote restaurant next door was not yet open, so I stopped at a rest stop along the autoroute and fired down an espresso. Then I put my foot back down on the floor again and bore down on Hendaye. The rain had stopped during the night and the day dawned to bright sunshine and mild temperatures that quickly turned downright warm.

I’d managed to run Jonathan Williams to ground several weeks earlier in Portugal where he was vacationing with his lady friend, Linda. The only place I could fit him into my schedule and me into his was Hendaye, where he and Linda were going to be staying for several days. At the end of the autoroute, I followed the signs for Hendaye, and before long arrived in what turned out to be a beautiful little coastal resort. I’d called Jonathan on the road near Biarritz and he’d given me directions to the Residence Sokoburo, which I located without too much difficulty. When I drove up out front I found Jonathan and Linda waiting outside.

They helped me wheel the case up to their room, furnished me with a beer, and in two conversation-filled hours, Jonathan had signed the prints. There was barely time for me to wish I had time to relax and soak up the sunshine, before I was back in the car, headed for the Biarritz airport. I arrived with twenty minutes to spare, sprinted to the Air Inter flight to Paris, where I changed planes and flew on to London.

When I arrived at Heathrow Airport, I discovered to my dismay that the small luggage cart that had served me so valiantly throughout the trip as a means of transporting the case of prints, had been lost by the airline. This was my next to last stop, so rather than wait around and fill out the appropriate forms, I decided to abandon it, hoping it would end up in good hands.

Vic Elford had flown to London from Miami two days earlier, and had spent the time before my arrival visiting his mother and brother in Wales where his brother owns a small hotel. Vic was waiting outside the arrival terminal and we drove for half and hour in Vic’s rent-a-car through a cold and dreary London rain to David Piper’s house in Windlesham. Waiting for us there were David, Alistair Walker, Richard Attwood, and David Hobbs, along with various and sundry wives. Also in the group was Mike Wright, a longtime instructor for the Winfield Driving School, who among many luminaries, was responsible for teaching Alain Prost how to heel and toe.

After setting up a production line on the Piper dining room table, the five drivers signed the prints amid much story-telling and good-natured ribbing. Liz Piper produced a delicious lasagna diner when the job was completed, after which David Hobbs, Alistair Walker and Richard Attwood, who had a considerable distance to travel, drove off into the rainy night. David Piper then took me and Vic, accompanied by Mike Wright and Liz Piper, “out back” to show us his collection of race cars. There was a P2 here, a P3 there, the bodywork of another Ferrari hanging from the ceiling, and in an adjacent garage, an immaculate Matra 650, over which hung a brace of freshly killed pheasants. It was enough to make a vintage enthusiast go weak in the knees.

Liz had booked Vic and I into Great Fosters, a fabulous 16th century manor house-turned-hotel just down the road, and in front of a massive fireplace you could have parked a small Mack truck in, he and I had a nightcap provided by an ancient concierge who fit right in with the ball and claw furniture, oak paneling and ornate plaster ceilings. On showing me my room, he pointed out that the bathroom had recently been remodeled, commenting that the bathtub was rather small, “not big enough to swing a cat in”: a classic English expression.

The next morning Vic and I were up before first light and headed back to Heathrow. Vic’s flight to Miami left from that airport, but mine took off from Gatwick, so Vic dropped me at the Speedlink bus station, and in short order I was at the terminal where I caught a British Airways flight directly back to Baltimore. I’d been gone eleven days and covered over 10,000 miles.

The Thursday after Christmas I was back in the air again, this time heading for Arizona where I was to meet with Henry Greder, Chuck Parsons and Tony Adamowicz. Henry is a Frenchman who finished 8th in the 1970 race co-driving a Corvette with countryman Jean Peirre Rouget, and Scottsdale, where he now lives, seemed to be sort of a central location for the four of us to meet. I’d shipped all 500 prints (in two cases) to Phoenix a day earlier, and after the freezing weather in Baltimore I arrived in Phoenix to blue skies, brilliant sunshine and temperatures in the 80s. I rented a small van, picked up the two cases from air freight and while trying to find my way to the Raddison Resort in Scottsdale, again managed to lose my way, this time ending up smack in the middle of a Fiesta Bowl celebration in downtown Tempe.

Eventually I found the Raddison, checked into my room and called Henry. In two shakes of a lambs tail, he was at my door, along with two friends. One, Michel Germaine, is an avid motor racing enthusiast/fanatic, and also a collector/builder of 1/43 scale models. He’d brought several examples with him that had competed at Le Mans in 1970: the #3 Porsche Martini/917LH “hippie” car, the #8 SEFAC/Ferrari 512S “long tail”, and the #57 N.A.R.T/Ferrari 312P that Tony Adamowicz and Chuck Parsons had driven. Armed with several coffee table books on Le Mans, Michel wasted little time in pointing out the errors in decal application on the rendering of the #11 Sam Posey/Ronnie Bucknum N.A.R.T./Ferrari 512S long tail that I’d included in the BATTLE OF THE TITANS print. I’m firmly convinced that had I asked him, Michel could have told me the pressure in the left front tire of any car in the field that year, at any time during the race.

Tony Adamowicz, who’d flown down from Costa Mesa, joined the group a short time later, and for half an hour, as if transported by a time machine, we were back at Le Mans in 1970, while Henry, Tony and I replayed the race and the events that stood out in our minds. With 500 prints to sign for the first time, we were looking at more than three hours of work, so after Tony finished describing a hair raising spin during the night under the Dunlop Bridge, we took the two cases over to the lobby of the hotel where we found an appropriate corner and pushed three tables together. The third member of the group, Chuck Parsons, had driven from his home in Salinas to Los Angeles, then flown to Phoenix with his son-in-law. They had arrived as well and soon joined us. We set up another production line and between bites of food and sips of beer and wine ordered from room service, the three drivers set to work signing the prints.

The following morning I was up early. I had a 10:30 flight back to Baltimore and I wanted to swing by the UNELKO Corporation, which is headquartered in Scottsdale, and say hello to an old friend, Howard Ohlhausen. UNELKO manufactures RAIN-X®, which was one of my sponsors in the early 70s. The last time I’d seen Howard in 1977 Unelko was operating out of an old three-story brick warehouse in south Chicago where it stockpiled then sold bales of rags to the Orient. RAIN-X® was a minor sideline. Over twenty years the company had grown considerably. Howard had just moved into an ultra-modern, brand spanking new corporate headquarters the previous day which would have done IBM proud. Unfortunately I could only spend 10 minutes with Howard, which I’m sure was just as well with him, as he was still trying to find his way around the new building and arrange the furniture. After a sprint to the Phoenix airport, I dropped the prints off at air cargo and flew back to Baltimore.

The first week of the new year I was on the road again, this time to Hartford, Connecticut, where I landed in a raging snowstorm reminiscent of the one I’d encountered in Graz. Sharon, Connecticut (about an hour’s drive from Bradley Field) is where Sam Posey now lives, and due to the storm, there was little traffic on the road – although I did see a lot of snow-blowers. I made the trip to Sam’s without incident, where he and his wife, Ellen, waiting for me in their expansive studio. The eclectic collection of artwork, furniture and architectural models that was scattered about testified to Sam and Ellen’s varied talents.

I was scheduled to fly out of Bradley that evening at 6:30, as was Sam, who was headed to Detroit to do television commentary at that city’s auto show, so having arrived at 1 P.M., we were under the gun. In the next three hours Sam signed 357 of the 500 prints, then it was back to Bradley, and a return flight to Baltimore.

In mid-January I shipped the 53 prints that had been signed by 21 of the 25 drivers to Brian Redman in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, and within a week they were back in Baltimore with his John Hancock in place.

On my trip through Europe, I hadn’t been able to hook up with Jean Pierre Rouget, Guy Chasseuil or Willi Kauhsen, the last three drivers who needed to sign the prints, so I had somewhat of a logistical problem. As a result of advertisements in a number of publications, I had orders that needed to be filled. I decided the best plan at this point was to ship the 53 prints with 22 signatures to Europe, have the three drivers sign them, then ship them back to me. While in Paris, Gerard Larrousse had supplied Jean Pierre Rouget’s number, and with Vic Elford acting as interpreter once again, I finally managed to contact him. Coincidentally, Guy Chasseuil was planning to visit Jean Pierre in mid February, which would allow me to kill two birds with one stone. Through Eberhard Strahle, I’d also managed to finally locate Willi Kauhsen who was living in Aachen, Germany.

In mid-February I packed the 53 prints as carefully as I could, and with some trepidation, shipped them off to Jean Pierre Rouget in St. Laurent du Bois, France (near Paris). They arrived safely, and on February 26, he and Guy Chasseuil signed them. After being thwarted by a snowstorm on his first attempt to ship the prints on to Willi Kauhsen, Jean Pierre got the job done and they arrived safely in Aachen. Willi signed them immediately, then shipped them back to me in Baltimore where they arrived on March 4th. In a little less than 3 months, the 53 prints with the 25 signatures had traveled over 24,000 miles.

When I unpacked the prints, I laid one out and looked at the 25 signatures beneath the names of the drivers. For several moments I reflected on the fact that over 25 years ago the same hands that had held the pens (which I’ve since mounted and framed) used to sign the prints had also held the wheels of 14 race cars that had competed in what is now regarded as a classic event.

Because of the foul-up at Dulles airport where Northwest Airlines refused to ship the two cases as hold luggage, I still have 450 prints with a varying number of signatures on them. The drivers are all ready to sign, however this time around the airlines and freight companies are doing the leg work.