Once upon a time…

Isn’t that the way fairy tales normally start? Looking back some 23 years to the spring and summer of 1972, that’s certainly how this adventure seems.

My association with Porsches started in the late ‘50s when I was occasionally allowed to drive my father’s red Speedster from the main road to the house. In 1966, the summer after I graduated from school, I was assigned the enviable task of picking up his new 911 at the factory. Three other classmates were in the party, and with two of them behind the wheel of a rented VW fastback we made a Stuttgart-Strasbourg-Paris-Chartres-Tours-Beaune-Dijon-Geneva-Lausanne-Zurich-St.Moritz-Innsbruck-Munich-Salzburg-Cortina-Venice-Florence-Siena, banzai “cultural” run, eventually ending up at our family’s summer home on the Mediterranean coast, in Porto Ercole, Italy.

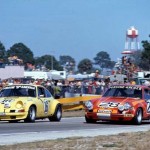

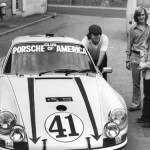

In 1969 a good friend named John Shaw had been at the Sebring 12 Hours and returned to Maryland with a hearty endorsement of the sport of motor racing. The next thing I knew, the two of us had bought a 1967 911S, converted it for 2-Liter Trans-Am racing and prevailed on Bruce Jennings to drive it. At the end of the season, I took the car to a PCA event at Marlboro, attended an SCCA school at the same track later that fall and another the following spring at Bridgehampton. There was no looking back after that, and for the next two years I drove the car under the team name, Toad Hall, in SCCA regional and national events, the first IMSA races, and the Daytona 24 Hours, Sebring 12 Hours and Watkins Glen 6 Hours.

At the end of 1971 the new 2.5-liter cars were introduced by Porsche, and I placed an order for one. Figuring it would be helpful to show my face in Zuffenhausen, I took a trip to the factory in mid-December with Franz Blam. Franz had just taken over as service manager at North Lake Porsche-Audi in Tucker, Georgia, and had agreed to oversee the preparation of the car. Somewhere over the Atlantic on the way to Germany, the idea I’d been kicking around for some time crystallized in my mind. Since being bitten by the racing bug two years before, I’d made it an almost personal crusade to try and explain what a fantastic sport motor racing was to the uninitiated.

To that end, I’d spent much of that time hopscotching around the United States and Europe, taking photographs for what would eventually be a photo essay on the sport entitled The Speed Merchants. Work on this book was nearing completion, and I thought the logical progression was a documentary film along the same lines. I’d seen a one-hour network television special on stock-car racing called The Hard Chargers that had the cinema verite look and feel that appealed to me, and had tracked down one of the producers in New York to discuss possibilities. Why not, I thought, take the new Porsche, race it in a number of the Manufacturer’s Championship events, and at the same time make a documentary film about the series. Where allowed, I could also use it as a camera car. It all seemed so logical at the time, not to mention that I felt money could eventually be made on the distribution of the film, Bruce Brown’s surfing classic, Endless Summer, still being fresh in my mind.

Arriving at the Porsche factory with Franz, we were met by Jürgen Barth, who was working in what I came to know as the “sports department.” Our car was in production and I snapped a few shots of it in the metal shop where wider fender flares were being mated with the stock body. We were also allowed to inspect one of the new 2.5 injected engines. Before leaving, I made an offer to Jürgen, who was already following in his late father, Edgar’s, footsteps as a driver, albeit on road courses, not in hillclimbs. Would he be interested in driving with me in some of the races in 1972? I told him about my idea for the film, and his immediate response was positive. We agreed to communicate over the next few weeks, and with that, out the door we went, back across the Atlantic.

Between the last week of December and the first week of January I moved ahead with what now seems like mind-boggling speed, assembling an entire New York-based film production crew and making plans to both race and film at Daytona, Sebring, the Targa Florio, the Nurburgring, Le Mans and Watkins Glen. I’d already asked Bob Beasley of Richmond, Virginia, to drive with me at Daytona, which was a six-hour event that year, but Jürgen agreed to come on board at Sebring and co-drive in the remaining events. We ran into problems at Daytona and DNF’d, but the weekend wasn’t a complete loss. Hans Mandt, who had worked for Peter Gregg for a number of years, decided to abruptly part company with him and, before the race was over, Hans agreed to come to work with me. Franz, whose job at North Lake would have prevented him from making the trip to Europe, graciously stepped aside.

Working out of the garage at his house in Jacksonville, Hans prepared the car for Sebring. Being a member of the PCA, I decided to run a Porsche Club of America windshield sticker in all the international events, which we did. The rough Sebring airport circuit took a toll on something that escapes my mind, and again we DNF’d, this time Jürgen and I driving together. After filming the first race at Daytona with a small crew, including shooting some footage from the race car, Toad Hall Productions, as the company was called, launched an all-out assault on Sebring. I can’t remember the exact number in the company’s employ, but there must have been 30 or more “toads” poking cameras and microphones in every nook and cranny of the airport circuit.

Before the Daytona event I’d written personal letters to all the team managers and principal drivers for Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Lola and Mirage explaining what it was I was trying to accomplish by making the documentary film, and enlisting their help. Basically I asked them to “act natural” when they saw us lurking around. To our pleasant surprise, we found most of them were genuinely interested in helping, not the least of which was Peter Schetty, the Ferrari team manager. We’d received permission from him for one of our camera crews to place lights around their garage in anticipation of shooting the night-before-the-race engine changes and other preparations of their three-car team. The camera crew hadn’t finished mounting the lights when the Ferrari mechanics were ready to leave for dinner, so amazingly Peter handed the keys to the garage to the production manager, told him to lock up when they were finished and bring them to him at the restaurant where they’d be eating!

After Sebring, we had a little more than a month to prepare the car for the three European races, having made arrangements to ship the car inside a small slant-bed GMC transporter, from Jacksonville to Hamburg. We were running Firestone tires at that time, and, in addition to taking spare parts, and a spare engine and transmission, we packed in as much rubber as we possibly could. Hans was to fly to Frankfurt, take a train to Hamburg and return to Stuttgart with the transporter and race car. Actually, the base of operations was to be the Max Moritz dealership, south of Stuttgart, in the town of Reutlingen. For personal transport during the month and a half I was to be in Europe, and also to use as a practice car for the Targa Florio, I’d arranged to purchase, through Max Moritz, a second 2.5-liter “lightweight” or rally 911. Both the race car and the rally car were bright yellow, the color my Toad Hall cars had run in for the past two years.

On the appointed date, I flew to Stuttgart, met up with Jürgen at the factory and drove out to his house where I met his mother and sister, both of who couldn’t have been kinder. Hans had just arrived from Hamburg with the transporter, and we unloaded the car in Jürgen’s driveway to check and see how everything had weathered the ocean voyage. The car and equipment inside was just as Hans had packed it, so we celebrated with a feast prepared by Mrs. Barth with much discussion of the upcoming Targa Florio, which Rirgen’s father had won in 1959. On the wall in the den was the beautiful sculpted bronze “Targa,” or plaque, that was presented to him as the winner of the event.

The plan of attack for reaching Sicily was for Hans to head south over the Alps to Italy with the transporter the weekend prior to the race. A young American named John Russell, who was working with Jürgen in the Porsche sports department at the time, would go with him, as would John’s girlfriend, Martha. Airgen and I were going to stop off in Monaco for the Grand Prix, then proceed from there around the coast and down through Italy, meeting up with Hans, John and Martha in Naples on Monday night where the overnight ferry left for Palermo.

Working at the Porsche factory, Jürgen’s street car was, quite naturally, a 911, and as luck would have it, also yellow. So on Friday afternoon, Jurgen in his 911, and I in mine, headed for Monaco with plans to spend the night en route. Around dusk, I followed Jürgen up and down through a twisty section of road that he told me, on reaching the hotel, was used as a special stage in the Monte Carlo Rally. I could only imagine what it would be like in the dead of winter, covered with ice and snow.

We hooked up with one of our film crews that was at the Monaco Grand Prix to shoot some footage, then after watching Jean Pierre Beltoise win the race in a BRM in heavy rain, Jürgen and I set out on the next leg of our journey. We planned on driving as far as Porto Ercole that night, the small fishing village on the east coast of Italy, about a hundred miles north of Rome, where the family home was. It was still raining when we set out, and after following the coast road and crossing the border into Italy near San Remo, we took the Autostrada around the top of the boot and down past Genoa. I remember distinctly Jürgen and I leapfrogging each other as we blasted in and out of the many tunnels interspersed along the route, going from the pouring rain and slick road surfaces into the lighted dry of a tunnel, then shooting out again into the rain. The tunnels stopped and the road gradually leveled north of La Spezia, and with our left-hand blinkers on we drafted each other at triple digits on down the boot.

Around midnight we were flagged over to the side of the road by a pair of jack-booted carabinieri with the complaint that our driving lights were too bright. I spoke fairly fluent Italian and understood exactly what the problem was, but decided the best policy was to play dumb and, in English, plead ignorance of any offense. After five minutes of non-communication, the carabinieri tired of the game and sent us on our way with disgusted shakes of their heads. A short time later we arrived in Porto Ercole, where we had no trouble falling dead asleep.

The next morning we woke to a brilliant Mediterranean sun, and after giving Jurgen a quick tour of the beautiful little village, we headed south for Naples. Two of my old friends from Porto Ercole and their wives made it a three-car caravan as we skirted around Rome and arrived late that afternoon in Naples. I’d been forewarned that this was the only city in the world where your wheels could be stolen from your car…while it was moving…so we made our way directly to the port, where we were happy to find Hans, John, Martha and the transporter.

The three of them had some harrowing tales of their trip over the Alps, the filly-loaded GMC with an automatic transmission, being less than ideal in the braking department. Several times, Hans said, the brakes had heated up to the point they were all but nonfunctional and he was fully prepared to abandon ship at any moment if he hadn’t found a suitable run-off area.

The overnight ferry from Naples to Palermo was one of the “Kangaroo” line of ships, and, in addition to us, there were several other racing teams “in the pouch.” Shortly after pulling out of the port, we sat down in the dining room with the Bay of Naples, Sorrento and the blinking lights of the Amalfi coast as our backdrop.

The following morning we arrived at the port of Palermo, disembarked and drove out along the coast road to Cefalu, another picturesque fishing village, where we checked into our hotel. The entire film crew had arrived in Palermo the previous day by air, and between their number and our team, we managed to turn the place into a temporary Toad Hall, the yellow-and-black stickers with the old English print being much in evidence. Trying to explain in Italian what Toad Hall meant to the hotel employees and other guests was a chore in itself.

On arriving at race headquarters in the pit area, which was on the course a few kilometers north of the small village of Cerda, we received a nasty bit of news. Earlier in the winter I had written to the Automobile Club of Palermo, the organizing body, requesting an entry for the race. A month or so later I’d received a typed reply in broken English, telling me that the automobile club was honoring my request and would accept my entry. Not having received any type of official entry form and knowing how Italians can be a little lax on details, I figured my mission was accomplished, and I hadn’t given it another thought.

In fact, an official entry form should have been filed, and we were told that the deadline for entries had passed. Consequently, we would not be able to race! The fact that we had traveled thousands of miles and spent a considerable amount of money to do so didn’t seem to cut any ice with the officials. They were nice, but firm, however agreeing to cable the authorities at the FIA in Paris and see if they would grant a waiver. The cable would have to be sent from the automobile club office in Palermo, which was 40 miles away, and since no business was conducted between l and 4 P.M. (after all, a man has to eat) the cable could not be sent until late afternoon. In the meantime, we were free to practice. Of course, anyone with a car, or donkey, for that matter, was free to practice, as all but one day, when the official qualifying runs were held, the roads were open, and shared with Fiat 500s, tour buses, pedestrians and sheep, not necessarily in that order! So, trying to come to terms with learning the course, Jürgen and I set out in our respective 911s, with road maps firmly in hand.

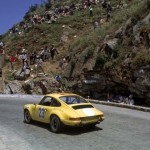

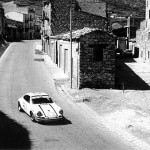

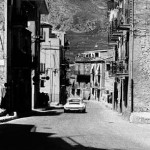

From the pit area, the road climbed gradually to the town of Cerda, where the three-car Alfa Romeo team had set up shop in one of the local garages. The road ran in pretty much of a bee-line through the center of Cerda, then continued to climb for some time through the rolling hills before dropping down through some wooded glades to the valley floor, climbing again through a number of switchbacks and a rock quarry to Caltavuturo. The traverse through Caltavuturo was more winding than Cerda’s, with high walls and rock faces which were used as grandstands on race day. Another section of twisting road led through the countryside to the town of Collesano, followed by another serpentine stretch to Campofelice before dropping down to the sea where a long straight led to a diabolical series of high-speed sweeping turns, before beginning the climb back into the mountains and the pit area. From start to finish the course measured 44.73 miles, and after one circuit it was apparent there would be ample opportunity for a fuori strada or “out-of the-road,” as accidents are referred to in Italy.

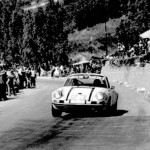

Based on previous years, we knew our times should be in the neighborhood of 40 minutes, so after taking over an hour to make the first circuit, it was obvious our work was cut out for us if we were going to chop off 20 minutes. After several more trips around the course in our street cars, Jürgen and I took turns putting the bit between our teeth, and took the race car out. By the end of the day, we’d survived numerous close calls with the ever-present tour buses coming in the opposite direction and were beginning to feel somewhat comfortable with the task at hand. The local farmers and shepherds were some of the most enthusiastic fans, waving us on around corners if the coast was clear. I did note that when possible the Alfa team went out in pairs, so if one of the cars did “leave the road,” the driver of the other would at least be on the scene to give whatever assistance he could. The drivers of the lone 312P Ferrari in the race, Arturo Merzario and Sandro Munari, had no such safety valve and were on their own if it came to extricating themselves from any wreckage. There was an autostrada that cut down through the middle of the course, and in some instances, cars would run half the circuit then blast back down this highway to the pits or garage to make any needed adjustments. Once on the scene, there was no need to load the race car up on the transporter at the end of the day, as you were free to drive it wherever you wanted.

During the first day of open practice, we were left to twist slowly in the wind by the Automobile Club of Palermo, which had yet to hear back from the FIA in Paris about whether or not we would actually be allowed to race. So, for all we knew, the practice we’d done might be for naught. Regardless, both Jürgen and I agreed, it was a hell of a lot of fun! On one of the circuits, we had mounted an Arriflex 16mm camera with a 10-minute magazine on the hood of the car in order to get some car-mount footage. Halfway around the course I was passed by Rolf Stommelen in one of the Alfas. Much to my surprise and delight, rather than taking off immediately, he allowed me to follow him for a kilometer or more to get some good action shots. Finally, with a wave of his hand, he stepped on the gas, and within several curves he was out of sight. It would only be months later when we returned to New York and viewed the film that we found much of it unusable. After several minutes of beautiful footage, the lens would suddenly explode in a red smear as we witnessed the “death of a bug.”

Toward the end of one circuit in the race car, I came on an Italian driver named Carlo Facetti who was driving a 2-liter Abarth prototype. His car had apparently broken down and he was on the side of the road with his thumb out, looking to hitch a ride back to the pits. I pulled over and he jumped in. There being no seat, he wedged himself into the back of the car, grasped the roll cage with both hands and I’m sure gritted his teeth as I completed the lap at race speeds. In later years when I ran into him on the circuit, we always had a good laugh about the wild ride I’d given him, which he said had deterred him from ever again hitchhiking.

On Wednesday, we continued to run the circuit in both the race car and our street cars, and after lunch at a restaurant in Cerda where the entire Alfa team sat at one long table, Carlo Chiti at the head, Vic Elford agreed to take me and one of our sound men around the course. We rigged up a headset for Vic, and driving his Alfa street car, he chauffeured us around, talking the whole way about what to look out for in the way of road surface changes, significant landmarks, etc., that was a great help in trying to piece the altogether similar, yet different, 44 miles together.

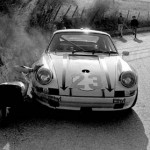

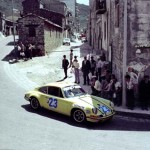

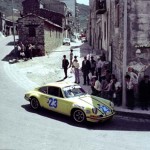

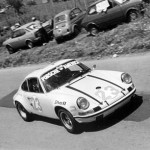

Although official qualifying runs were set for that Thursday, the local firefighters decided that this would be an advantageous time to hold a one-day strike, with threats of it lasting longer, to extract whatever demands were currently on the table. During this additional day of practice, Jürgen had a small fuori strada with the race car, understeering into a wall. The damage was only cosmetic, and back at out hotel, Hans quickly and efficiently put things back in order. Thankfully, by that Friday, the day of official timed qualifying, the firemen having settled their dispute, word had finally come from Paris that they would make an exception to the rule and allow us to race. So the officials gave us our baby-blue number 23, which we quickly applied to the car before they had a change of heart.

I was first up for qualification and took off from the start/finish line with a 16mm Bolex camera mounted to the rear of the race car. On entering Cerda, I was somewhat shocked to find the streets deserted. Up until then, whenever we reached one of the villages on the circuit, we would slow down and idle through as the streets were filled with people and everyday traffic. Now, ahead of me was a long undulating asphalt ribbon sandwiched between the buildings. Although cleaned by the street sweepers with their brooms, the surface of the road was still somewhat dusty, so I had no idea how fast I could safely go, and as for a breaking point at the far end, I’d never established one.

I managed to make the one lap without any major incidents, turning the car over to Jürgen so he could have his go. When all was said and done, we had qualified with a time of 40 minutes, 37 and 6/10th seconds, a full seven minutes behind the Ferrari of Merzario and Munari who had clocked a 33 minute, 59 and 7/10ths lap to take the pole, such as it was. Vic and Gijs van Lennep were next, less than seven seconds back. So, whatever happened to us, it looked like it was going to be an interesting race for the overall win.

Saturday was a free day for final practice and preparation, and on Sunday morning we were up at the crack of dawn to get to the pits before the roads were closed. The whole week the weather had been picture-perfect and race day was no different. As we drove to the pits, we could see that large crowds had gathered along the sides of the road and up in the hills. Many large banners were in evidence inscribed with NINO, for local favorite Nino Vacarella, who was driving one of the Alfas with Rolf Stommelen. In many places his name had also been written in paint on the road surface itself, or on the sides of buildings. One might have thought that the town of Collesano, where Vaccarella was born, was actually called NINO.

We had six camera crews scattered around the circuit, each one assigned a local interpreter, and after explaining to the gentry in the towns what it was we were doing, they were invariably invited into the houses and given the run of the place, enabling them to get some great shots of the race cars from balconies and terraces as they passed through.

I can’t remember how Jürgen and I decided who would start, but I suppose since it was my car, I decided to get my licks in first. Some 76 cars were lined up on the road that passed through the pits in order of qualification. We were up toward the head of the field, there being many slower local entries. I strapped myself in and waited as the cars ahead of me were flagged off with great ceremony at 15 second intervals. Even with a 44-mile circuit, when you calculate the number of cars in the race and the time between each start, the mathematics show that it wasn’t long after the last one left that the first one was completing the initial lap. This was the last thing on my mind when the flag fell.

Soon after the start I was at Cerda, and again, although this time I was aware of the crowds of people packed between the buildings, the narrow empty street ahead was somewhat unsettling. I tried to control the urge to take advantage of this stretch of straight road and at the same time figure out where I should start braking for the sharp curve at the exit to the town.

Once out of Cerda, I began to get into a rhythm, many of the landmarks now being more familiar. It’s best to learn it in sections, Vic had told me. Use a farmhouse or a distinctively-shaped tree as a marker to remind you of the start of a section, then remember the next 10 curves or corners. Once you’re familiar with one section, you can tack it onto another section and another section until you’ve got the entire circuit broken down into sections.

Along the entire length of the road, there were large groups of people, some of them sitting on walls right at the edge of the course, seemingly unfazed by the cars that were speeding by within a foot or two of them. The more daring, or perhaps intoxicated, fans even emulated matadors, literally leaning out and waving flags in front of me as I passed. A number of American flags were in evidence, and I could tell the Porsche Club of America signage across the top of the windshield really gave them something to identify with and cheer for.

Somewhere between Cerda and Caltavuturo I finally managed to catch the car that had started ahead of me, in this case another 911 that had a Liqui Moly sticker on its rear bumper. Having reeled him in, I stuck the nose of my car within a few feet of his hindquarters and continued to hound him for several kilometers. I could see that my presence had not gone unnoticed, as he was continually looking in his rearview mirror. From Vic’s instructional ride around the course, I remembered that we were approaching a tricky spot where the road made a radical fork to the left after cresting a sharp rise. Of particular significance was the fact that the road surface changed from a sticky new asphalt to an older and slicker section. I was obviously much on Mr. Liqui Moly’s mind by this time, having been behind him now for a good five minutes. As we approached the fork in the road, I backed off slightly in anticipation of the road surface change. Liqui Moly, on the other hand, kept the pedal to the metal, and on cresting the rise, had forgotten about the fork. With much delight, I watched as he locked his brakes and slid straight off the road into a freshly cut hayfield. Thank you, Mr. Elford, I thought to myself.

I did two laps and then turned the car over to Jürgen, telling him hurriedly that everything seemed to be operating perfectly. It was a hot day, and after 88 twisting turning miles, I was ready for a break, a drink of acqua minerale and a sandwich. Erminto, Piero, Paola, and Emilia, my friends from Porto Ercole, had decided to watch the race from the pit area, so there was much back-slapping and story telling about the first two laps, including the running to ground of Liqui Moly. Although it was a little hard to determine what position we were in, based on the non-stop discourse that the female PA announcer was spewing forth, the general consensus was that we were moving up in the field.

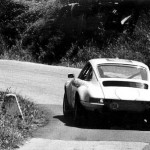

Jürgen did his two laps without incident, and turned the car back over to me. I did two more, becoming more and more familiar with the circuit each time around, and when I pitted the second time, we changed all four tires, more for insurance than necessity. Although we carried a spare tire and jack with which to make a change out on the circuit, it was obviously something we wanted to avoid. After Jürgen pulled back on course, I remember the PA announcer telling the crowd how the American crew of car number 23 had changed all four tires with “supersonic” speed, our team being one of the few, aside from those of the Ferrari and Alfa factories, that was using air wrenches.

With our car passing the pits once every 40 minutes, most of the time in between was spent waiting and wondering how things were going out in the countryside, along with a healthy dose of hoping all was well. As our stopwatches ticked toward 40 minutes, we all held our breath and watched for a yellow 911 to come into view. Sure enough, right on schedule, Jürgen flew by the pits and headed into our eighth lap. Not having missed a beat up until this point, we were ecstatic to find out that we were in sixth place! I took a final drink of water, strapped on my helmet, and prepared to take over for the last two laps.

When Jürgen came in, a little behind schedule, we were dismayed to see that the right front of the car was in disarray. For whatever reason, he had another fuori strada, but this time the damage was much more severe. As John Russell refueled, Hans set to work with a pry bar to straighten out the badly crumpled fender. Thankfully, the tire had not been cut, and again the damage was largely cosmetic. Even so, the officials in charge of the pits refused to let us rejoin the fray until the fender had been pried out further than was really necessary, which cost us a good minute or two.

With the repairs finally made to the satisfaction of the powers that be, and a new tire on the right front, I took off hell-bent-for leather, determined to try and make up the time we had lost. It didn’t take more than a fast sweeping curve or two for me to confirm that the suspension had not been damaged. Driving like a man possessed and managing to keep it between the ditches (and away from the walls) I completed what turned out to be our final lap, nine in all. On receiving the checkered flag I was directed to the impound area and told that the car must remain there until the officials did whatever officials do after a race.

I thought nothing of it, and made my way back to the pits where the rest of the team was celebrating our finish. Eventually we loaded up the transporter and were ready to head for Palermo to catch the overnight ferry back to Naples. It was scheduled to leave at 6:30 that night and it was almost 5. In spite of our protests that tempus fugit, the “poobahs” of the Automobile Club of Palermo refused to release the car. If we took the car out of the impound area before it was officially released, we would be disqualified, they told us.

Things were starting to get serious now. The next race, the 1000 Kms of the Nürburgring, was the following weekend. In addition to making the trip back up the boot of Italy and over the Alps to Stuttgart, considerable bodywork was needed to get the car back in shape. If we missed the Sunday night ferry, the next one would not leave until the following evening, putting us squarely behind the 8-ball timewise. Becoming more and more agitated with the officials, who still refused to budge, I told Hans and Jürgen to head for Palermo. I’d wait with one of my Italian friends and drive the race car and my road car, over the public roads, and join them when the officials finally let us go. If they kept us so late that we missed the ferry, we’d head for Messina, on the western tip of Sicily, and take one of the boats, which ran more frequently, across to the Italian mainland, then drive up to Naples and meet them there. It would be a desperate move, but these were desperate times!

Half an hour after Hans, in the transporter, and Jürgen in his 911, had left, the officials finally released the race car, having not so much as looked at it the entire time. It was 5:30 and we had exactly an hour to make the 40-mile drive to Palermo in bumper-to-bumper post-race traffic. With my Italian friend in my road car, I jumped back into the battered race car and set out on the coast road. Driving like a madman, often on the shoulder of the road, and passing cars left and right, many of them occupied by race spectators who were no doubt surprised to see one of the cars that had hours ago been competing, we managed to reach the dock where the ferry was tied up just as the gangway was about to be raised.

Once on board, and underway, we continued the celebration where we’d left off several hours earlier, eating plates of spaghetti and washing them down with bottles of Sicilian wine. We found out we’d finished in 10th place, having lost four positions in the pits. Merzario and Munari had won in the 312P Ferrari, but the real story of the race was Helmut Marko in one of the Alfas. Starting the next to last lap, the Ferrari had a 2 minute and 21 second lead but, at the finish, Helmut had closed to within 16 seconds. He’d covered the final 44 miles in 33 minutes and 41 seconds flat, faster than the Ferrari had qualified. The all-out lap record was still safe, however, and remains to this day, held by Leo Kinnunen in a Porsche 908/3 at 33 minutes and 36 seconds.

As a memento of the race and our 10th place finish, Rirgen and I both received miniature “Targa” medallions, identical to the one his father had won 13 years before. It now hangs in a frame on the wall of my office, and, looking at it from time to time, I can’t help but remember what a unique and fun experience this mad affair called the Targa Florio was, and how there’ll never again be anything like it.

After rising at 5 A.M., racing for 6 1/2 hours through the Sicilian countryside, battling with Italian races officials and consuming a substantial amount of wine, the sandman on board our Palermo to Naples ferry paid me a visit in short order once I returned to my cabin. When we arrived in port the next morning and disembarked, we began the sprint back to Stuttgart in order to prepare for 1000 kms of the Nürburgring the following weekend.

I neglected to mention that I had hooked up with motor racing journalist Pete Lyons at the Targa. Several months earlier I had shipped a new Honda 750 motorcycle to England where Pete had picked it up. I had agreed to let him drive the bike through Europe, attending several races, and ultimately deliver it to me in Sicily. After over a thousand miles of trouble-free two-wheeling, fate was waiting around one of the corners near the town of Cerda. Pete hit an oil slick and dropped the bike, doing little harm to himself, but leaving the Honda a little worse for wear. There was damage to the exhaust system, various scrapes here and there and a set of handlebars cocked at a precarious angle. My Italian friend, Piero Rispoli, was assigned the unenviable task of driving the bike several hundred miles back to Porto Ercole in its warped condition. Airgen and I wished him good luck, told Hans and the rest of the crew we would see them back in Stuttgart, god-willing and the brakes on the transporter cooperating, then jumped into our respective 911s and began the dash north.

Practice for the Nürburgring was scheduled to start that Thursday, and by Tuesday evening Hans and the transporter had arrived at the Max Moritz dealership in Reutlingen. Working throughout the next day with several men from the body shop, he’d repaired the damage to the right front corner, pulled the motor and changed the gear ratios, and gave the rest of the car a thorough going over. Although we had a spare engine, we were saving that for Le Mans, and as there was no evidence of metal on the oil plug when it was drained, we felt confident it would hold up for practice and the race.

The Eifel Mountains, where the Nürburgring is situated, is approximately 180 miles northwest of Stuttgart as the crow flies. Visions of the famous circuit danced in my head on the drive there, as during my three-year love affair with motor racing I’d read countless stories and seen numerous photographs of the track, and perhaps more so than the Targa Florio, had built it up to mythical proportions in my mind. The weather forecast for the coming weekend was not encouraging, and when we turned off the autobahn and began the gradual climb into the Eifels, the mist we first encountered turned to a steady sprinkle. Before leaving for Europe I’d pitched the folks at RAIN-X for sponsorship, and we’d brought several cases of the “invisible windshield wiper” with us. If nothing else I figured after the sunny weather in Italy we’d finally get a chance to test the product under racing conditions.

Compared to the other drivers in the race, I knew I’d be at a decided disadvantage, having only seen a map of the circuit. The prospects of learning the twists and turns of this 14-mile roller coaster were daunting enough without throwing slipping and sliding into the equation. Thankfully, by the time the first practice session got underway, the rain had stopped and the track surface was drying. Compared to the Targa where the front-running cars consisted of the winning Ferrari and three Alfa Romeos, the field for the 1000 Kms was more substantial: three Ferraris, two Alfas, a Mirage, a Lola, a 908/3, a number of 2 liter prototypes, several Ford Capris and a pack of 911s.

Having raced there many times before, Jürgen took the car out first. The 3-liter prototypes were turning 7 minute and 40 second laps, and if memory serves correctly a 2.5 911 was two to three minutes slower, somewhere around nine to 10 minutes. Consequentially, once your car passes the pits, there’s not much to do as the seconds tick by but shuffle around and check the stopwatches. After several laps, Jürgen was back in the pits, reporting that everything seemed fine in the engine, transmission and suspension department. With some trepidation, I slid behind the wheel and pulled onto the course.

During the first lap, I had my hands full just following my nose around the mile after mile of sweeping up-and-down curves, dips, dives, humps, and switchbacks. The only section I recognized from what I’d read in books and seen in photographs was the Karussell, a semicircular, mildly banked concrete affair that you dropped in and popped out of 180 degrees later. The long straight leading back to the pits was also somewhat familiar, although I wasn’t prepared for the series of disconcerting humps interspersed down its length that threatened to launch you skyward when cresting them. This is what reportedly happened to Finnish driver Hans Laine two years before while driving a 908. He had crashed heavily in practice while scrubbing tires, the car immediately bursting into flames, and in spite of the efforts of other drivers who stopped to try and help, the fire was too intense and poor Laine had perished.

Throughout the first practice session, I spent almost as much time looking in the rearview mirror as at the road ahead, trying to keep out of the way of the faster cars. Hans Stuck and Jochen Mass were both driving factory Ford Capris and at one point while running together they passed me, nose to tail, on the outside of a fourth gear downhill sweeper. On paper these cars were somewhat faster than a 911, but that didn’t lessen the intimidation factor any. Toward the end of the session, John Fitzpatrick, who was co-driving with Erwin Kremer in a car identical to ours, came out of the pits ahead of me. For half a lap I did my best to keep up with him, trying to duplicate his braking points and lines through the corners. I also tried to heed Vic Elford’s advice from the Targa; learn the circuit in sections, then string those sections together. At the end of the first day of practice, thanks to Jürgen, we were well in the hunt with the other 911s.

The Toad Hall film crew had made the trip up from Sicily and had been busily at work in the pits and out around the circuit. The ADAC officials who ran the show at the Nurburgring, however, refused to allow us to mount cameras on our car during the practice sessions, so we were denied any footage of the historic circuit from a driver’s viewpoint. During the remaining practice sessions and qualifying on Friday and Saturday it rained off and on, and as a result the track never fully dried out. If nothing else it helped define the line through the turns as this was the only part of the surface that was ever totally dry.

Sunday morning we again woke to rain, and as I ate breakfast in our hotel I was forced to contemplate what the track would be like in the wet conditions. After three days of practice I’d come to terms with the Nürburgring and could pretty much run the circuit in my mind, tacking sections together one after the other. Even so, I was still no match for the German drivers in the other 911s who knew their way around the course like I did Mid-Ohio or Lime Rock.

As if on cue, it stopped raining shortly before the start. The going would still be slippery, so we chose to start on intermediate tires. It didn’t take a genius to figure out we’d be better off with Jürgen doing the first and last two-hour stints with me taking the middle portion. Fifty-one cars made an abbreviated pace lap around the loop south of the pits, then blasted off into the Eifel Mountains. This is the only time during The Speed Merchants that the Toad Hall car makes a cameo appearance. After the start, the cars pop over a rise in military order and turn right off the screen, the windshield wipers of the sedans beating furiously. For those who have the film, Jürgen is in number 65, the yellow 911.

The first two hours were uneventful, Jürgen gaining several positions both on the track and due to attrition. By the time he pitted, the road surface had dried considerably and we changed to dry tires. I managed to do my two hours with a minimum of dramas, but towards the end of it began to feel nauseous. It was probably a combination of the bratwurst I’d eaten earlier and the undulations of the course, there being several places where the car became all but airborne, leaving my stomach (and the bratwurst) hanging in midair. After turning the car over to Jürgen, and with my feet back on solid ground, I recovered quickly.

The Ferraris finished first and second, Ronnie Peterson and Tim Schenken winning, and we ended up 13th, behind three other 911s. Although Jürgen had done the bulk of the work, I’d managed to hold my own, we’d finished, the car was in one piece and we had a full week to prepare for the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

During that week Hans was headquartered in Reutlingen, again working out of the Max Moritz dealership. I took up temporary residence at the Hotel Buy (pronounced BWEE), just around the corner from the factory in Zuffenhausen. The place was run by a friendly chap who took great pride in showing off his guest book that was filled with the names of famous Porsche factory drivers. With genuine sadness, he pointed out Jo Siffert’s signature and a cartoon of a 917 the Swiss driver had penned. Instead of puffs of exhaust spewing from the tailpipe, Jo had written “Buy, Buy, Buy.” Sadly, he’d lost his life the previous year driving a BRM in a Formula 1 event at Brands Hatch.

I spent most of that week either in Reutlingen or at the sports department in Korntal, which was a short distance down the road from the main factory. While at the sports department I got to know the inimitable Frau Baer, whom I’d met briefly the previous December. Although she retired some time ago, the many Porsche owners who dealt with her over the years will undoubtedly never forget her. Dressed in a white smock with her hair in a tidy bun, you felt as if you were talking to a kindly grandmother when ordering parts or enquiring about the latest tweaks. She had a computer-like ability to remember hundreds, if not thousands, of part numbers in those days when personal computers were still 10 years off.

Just down the hallway from the sports department office was a large room that served at that time as the Porsche museum. Under Jurgen’s auspices, and within reason, I had free run of the place, and consequently spent a good hour or so looking over, sitting in and imagining what it would have been like to drive some of the cars in the collection. In my wanderings through the storage area I stumbled on a 10-piece set of aluminum boxes, large and small, which had been used the previous year by the Martini team. I purchased them at a good discount and immediately set to peeling off the Martini insignias and replacing them with Toad Hall stickers.

During this time the members of the film crew had dispersed to the far corners of Europe, one group going to England to film with Brian Redman at his home in Lancashire, another to Brussels with Jacky Ickx, and a third to Graz, Austria, with Helmut Marko. We still had a spare crew so I arranged for them to come to Stuttgart and shoot some film of Porches in production. We spent the better part of a day following the assembly line from start to finish. Sadly, nothing ever came of this footage.

I had a somewhat amusing (looking back on it now) experience one night during this week. It was the end of the day and Jürgen, John Russell and I were the last people to leave the sports department. John and I were to meet Jürgen downtown in Stuttgart later that evening for dinner, but we wanted to go back to the hotel first and clean up. Jürgen had already pulled away when John remembered he’d left something in the office. He didn’t have a key to get in, but he knew of a bathroom window that was open. I gave him a leg up, and a short time later, he reappeared and jumped out, having retrieved whatever it was he wanted. We drove back to the hotel and took showers before heading downtown.

No sooner had we walked out of the hotel and jumped into my 911 than we were surrounded by several squads of police, the blue lights of their vehicles flashing. Luckily John spoke rudimentary German, and one of the officers a little English. Even so, we were put up against a wall at gun point and summarily frisked. The police had received a tip recently that members of the Red Brigade were planning a terrorist attack on the Porsche factory. Apparently someone had spotted John crawling in and out of the window at the sports department, seen us get into our car and had called the police. The police had spotted our car outside the hotel and had waited until we came out to confront us. It took a good half hour for them to verify that John worked at the factory and I was a harmless American.

The plan for Le Mans was to run the engine that we’d used at the Targa and the Nürburgring in the first practice session, then change to the fresh engine for qualifying and the race. It was with both surprise and delight that Jurgen announced at dinner that evening that he had arranged for the loan of an engine from the factory. There was some question as to whether the bearings in the normal 2.5 engines would go the distance. The factory engine was 2.5 liters, but had a shorter stroke than the spare we’d brought and was therefore thought to be more reliable. It was through Jürgen that we had also obtained an entry for the race itself, the concession being that the car had to be entered under the name of Louis Meznarie, the owner of a local garage, and one of our co-drivers had to be Frenchman, Sylvan Garrant. So with the car having been fully prepared by Hans, we headed for France with high hopes.

I’d been to Le Mans in both 1970 and 1971 to take photographs for the book I was working on, so I was intimately familiar with the circuit itself having traipsed from one end to the other shooting every curve and corner. This time around, however, I was to be a participant, and the experience would be decidedly different.

In 1970 I’d been a member of David Piper’s 917 team and had stayed with them at the Hotel de la Cane in a small village called Sceaux sur Huisne which was on the main highway between Chartres and Le Mans. It was a quant little place that had a garage on the grounds, so I’d made arrangements earlier in the year for both the race team and the film crew to stay there, the film crew having reassembled with two valuable additions, Peter Samuelson and Jean Pierre Avice.

Peter was a young Englishman whose family owned Samuelson’s, a London film rental and production house, and Jean Pierre was a Frenchman who had grown up in Le Mans. Together they’d handled pre-production for the French portion of the shoot, Jean Pierre having worked on Steve McQueen’s film, Le Mans, two years earlier. Shortly after meeting him, he related the story of getting a call from the police in the middle of the night during the production with the news that they’d arrested one of the mechanics who was working on the film. The mechanic had gotten quite drunk at a local disco and decided to impress a girl he’d picked up by taking her for a spin in one of the Ferrari 512s that was being used in the movie. On arriving at the hotel, Peter and Jean Pierre gave each of the film and race crew a packet of materials that would come in handy in the event they ran into problems, not the least of which was the name and home phone number of the chief of police, who after the Le Mans shoot had become a friend of Jean Pierre’s.

The tales of going through tech inspection, or scrutineering, at Le Mans are legendary, the exercise being more one of ceremony than function. It would seem that the members of the ACO (Automobile club de 1’Oest), the organizing body at Le Mans, who are in charge of deciding who races and who doesn’t, and under what conditions, spend the entire year leading up to the event in eager anticipation of jerking the chains of competitors who have never experienced nitpicking in the Gallic tradition. Luckily, with Jean Pierre at the helm, we were able to communicate with the ACO officials, and technically being a French entry, we sailed through tech in less than an hour.

Because much of the eight-mile Le Mans circuit consists of public roads, which are closed for practice and the race, all sessions start late in the afternoon and continue into the early evening. I’d met our French driver, Sylvan Garrant, at scrutineering, and he seemed to be a nice enough fellow; tall and slightly balding with a word or two of English in his vocabulary. My knowledge of French was just as limited, but Jürgen spoke it fairly fluently, so we were able to communicate in a round-about way. Once out on the track in the first practice session, it was less than a minute before I was headed down the famous Mulsanne Straight.

Because of its sheer length (over three miles) and the many high-speed tales that are associated with it, this stretch of road had become bigger than life in my mind. I’d photographed it from one end to the other and driven up and down it in a street car, but now I was strapped into a race car with nothing but an unending ribbon of asphalt ahead of me. I’d driven at Daytona several times in 1970 and 1971, so I was familiar with sustained high speed in a 911, but, still, the first time down the Mulsanne, it seemed to go on forever.

The notorious right-hand kink toward the end, which had hardly been noticeable in a street car, suddenly became an actual curve. Although there was a fair amount of runoff area beyond the shoulders of the road, the twin-tiered Armco barriers lining the straight looked as if they could easily launch a car into the thick woods beyond if struck at the wrong angle. At the end of the Mulsanne the track made a sharp 90-degree turn past the signaling boxes before heading back in the direction of the pits.

There were two more long straights connected by fast sweeping right-handers, then the track took a fairly severe right-hand dive into the slower left-hand Indianapolis. A short chute led to the equally slow Arnage corner, beyond which another straight led to what in years past had been the infamous right-left-right flick known as White House. This section of track had undergone extensive redesign since the 1971 race, White House having been eliminated. In its place were a series of tricky third- and fourth-gear right-and left-hand off-camber sweepers, connected by short straights. The Ford Chicane at the head of the pit straight, taken in second gear, led to the run past the pits and a fast uphill right-hand sweeper. After cresting the rise under the Dunlop bridge, the track dove down to the left and right “esses,” then on to the tight right-hand Tertre Rouge corner and the downhill chute that put you back onto the Mulsanne, or Les Hunaudieres, as the straight is actually known.

My first impression of the track was how smooth its surface was, there being barely a bump to be found along its entire 8.47-mile length. Apart from holding on for dear life and gritting your teeth down the straight, learning the circuit seemed like child’s play after the Targa and Nürburgring. After several laps it was apparent that the new section of off-camber sweepers was going to be the most difficult section to deal with. If you didn’t get the first one right, you were set up wrong for the next one, and each one after.

Although Ferrari had backed out of the race at the last moment for fear of besmirching their perfect record, the powerful Matra team with the resources of the French government behind it was here in force, three 670s and one 660 Spyder having been entered for a multinational team of drivers. Alfa had three long-tail cars, and Jo Bonnier two Lola T-280s with detuned Ford DFV engines. Rounding out the cars believed to have an outside chance for an overall win was a long-tail 908 coupe rented from the Siffert museum and entered by Reinhold Joest. The rest of the field consisted of 908 Spyders, a 910, a 907, several Ligiers, and a healthy dose of 2-liter prototypes and sedans, among them nine Ferrari 365 GTBs and seven 911s, ours included.

Jean Pierre had received permission from the ACO for us to put cameras on cars during the practice sessions, and, in addition to our 911, we got footage from three other prototypes, including one of Jo Bonnier’s Lolas. We’d rented a helicopter with a special anti-vibration Tyler mount to get some aerial shots, and also had a 1,000mm lens on hand, which we intended to use for shots down the Mulsanne Straight. One of the trucks the crew was using was to be driven through the forest to the kink in the straight, giving us a platform from which we hoped to get some dramatic long-lens shots of the start. Jean Pierre had also arranged for two gendarmes on motorcycles to be at our disposal throughout the race so our camera crews could go anywhere they wanted unimpeded.

The day of the race dawned sunny, but the weather forecast called for intermittent showers starting early that evening. The late afternoon start time at Le Mans gave us plenty of time to get to the track, and, once there, ample opportunity for the pre-race jitters to build. I’d elected to start, Jürgen would take over next, and our French co-driver, Sylvan Garant, would follow. Promptly at 4 P. M. we were waved away on the pace lap, which was anything but that. We’d qualified 44th out of 55 cars in the race, and by the time I got around to the Mulsanne the cars ahead had strung out far ahead and for all intents and purposes we were racing. By the time I crossed the start-finish line, the rest of the field up front was well away.

Thinking back 23 years, I can’t recall anything dramatic that happened during the first two hours. We were one of the slower cars in the race, and the Matras, Alfas, Lolas, etc. seemed to constantly be passing us. The etiquette I adopted on the Mulsanne was to stick in the right lane and hope I didn’t arrive at the right-hand kink at the same moment as a faster car. If this happened, it took a concerted effort to cut the curve short and avoid drifting across to the left side of the track. Although I hadn’t been conscious of passing many cars, by the time I turned the wheel over to Jürgen we’d moved up to 32nd place.

It was just about this time that the first rain shower of the evening blew through and Jürgen pitted for rain tires. As I ate a Grand Marnier crepe and watched the cars on the track throw up rooster tails of spray as they sped by, I knew I’d probably have the unenviable opportunity of driving at Le Mans in the rain. Thankfully the English crew from Firestone had hand-grooved several sets of our slicks into what they promised would be “demon” rain tires. We had a two-way radio in the car for the first time which worked sporadically due to the length of the track, and each time he passed the pits Jürgen reported in that all was well. Sylvan took over, and two hours later when he handed the car back to me, also reported that there were no problems. The rain had stopped, but the track was still wet, so we changed to intermediate tires. As is the case with most 24-hour races, there was little chance of getting any real sleep. We had a small caravan back in the paddock and with three drivers had four hours off between stints. When I wasn’t behind the wheel, I rested nervously and perhaps caught an odd wink or two during the night, but never really slept.

In the early morning hours, the notorious ground fog I’d heard so much about reared its ugly head. Storming down the Mulsanne I’d suddenly rush into a patch, not knowing whether it was 10 feet deep or a quarter mile. Each lap it would move, so I never knew if it was the same patch or a different one. At some point I’d have to decide whether to lift, and invariably when I did, the fog would clear, leaving me wondering if discretion really was the better part of valor.

At around 8:30 the next morning we were still running strong, albeit in 25th place, and I was due to take over. During the night we’d gotten out of sequence and Jiirgen was in the car when it pitted. On exiting the car he told me that there had been an accident on the far side of the course and to be careful as there was debris on the track. When I arrived at the second of the two fast sweepers after the Mulsanne corner, course marshals were strung out along the Armco barriers furiously waving yellow flags. As I slowed I saw a set of long skid marks that led to the blackened hulk of a Ferrari GTB, that was up against the guardrail smoldering. The next time around, I noticed pieces of yellow fiberglass strewn along the left hand Armco, but no sign of another car anywhere.

It was only after the race that I learned Jo Bonnier, in one of the yellow Lolas with a Ford E DFV, had been the other car involved. According to Vic Elford, who’d been directly behind him in one of the Alfas at the time of the accident, Jo had pulled to the inside on the entrance to the a sweeper to pass the Ferrari driven by Frenchman Florian Vetsch. Vetsch hadn’t seen Jo and had a closed the door, clipping the front end of the Lola and sending it spinning into the Armco, which, rather than stopping the car, had launched it into the thick forest. At a speed of 150 miles per hour plus, poor Bonnier never had a chance and had been killed instantly. Vic Elford had pulled to the side of the road to try and help, but there was nothing he could do. After the race, Jean Pierre managed to get a copy of the French TV footage shot by a cameraman who happened to be in the area, which we ultimately included in our film. Unaware of what had happened at the time, I continued on.

Now, over the radio, I learned that we were just behind the only other 911 still remaining in the race. A short time later I spotted the car on the side of the road halfway down the Mulsanne, with its engine lid up. This good fortune was short-lived, however, because toward the end of my stint, while negotiating the tricky new section of off-camber sweepers, I managed to put my right-side tires in the marbles. Before I could recover, the car understeered off the track, sliding across the grass and into the Armco barrier.

To say I was chagrined was a gross understatement. I’d made a mistake, no matter how slight, and from the force of the impact I was certain our race was finished. Luckily, the pits were only a short distance away and I was able to limp in with the right front tire flat. Once out of the car, I saw that the damage was superficial and not as severe as it had felt. In short order, Sylvan was in the car and away.

I had two more turns behind the wheel, and each time I paid extra special attention to the line at the place I’d gone off earlier. I obviously hadn’t learned my lesson, because, two years later, driving a 3-liter Carrera in the 1974 race, I did the exact same thing, at almost the exact same time, at almost the exact same place! Luckily, it was once again superficial damage and we were able to finish.

I was behind the wheel when the checkered flag fell at 4 P.M., and in spite of my earlier off-track excursion, the last few laps were extremely satisfying. The track workers had left their posts and now lined the track as we passed with their flags waving. An enthusiastic group of Americans had been camping just after the Indianapolis turn and waved the Stars and Stripes wildly when I passed. As I pulled into the impound area, the heavens literally opened up and the rain poured down in torrents. The Matra of Graham Hill and Henri Pescarolo finished first, followed by a similar car driven by Francois Cevert and Howden Ganley. We ended up in 13th place, having covered 2, 413.19 miles at an average speed of 100.54 miles per hour, and due to the fact (I’m convinced) that we were running the short-stroke 2.5 factory engine, we were the only 911 to finish.

Looking back on those three races we did in Europe that summer of 1972, I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Jürgen Barth, who was instrumental in organizing so many of the logistics. Hans Mandt also deserves the lion’s share of the credit for the preparation of the car, not to mention hazardous duty pay for the many frights he undoubtedly suffered while crossing the Alps in the overloaded GMC transporter. At the Watkins Glen 6-hour race that July, driving with Bob Beasley, we came in seventh, and in the IMSA Camel GT series I ended up third. Looking back over that season and the number of races we were able to finish I certainly can’t complain.

As for The Speed Merchants, it ultimately took the better part of two years to complete, even though we finished filming shortly after the race at Watkins Glen. We’d shot 170, 000 feet of film, which translates to 70 hours, and from that eventually cut a 95-minute feature-length documentary. Without the help and cooperation of Mario Andretti, Vic Elford, Helmut Marko, Jacky Ickx, Brian Redman, and a multitude of other drivers, teams and race officials who participated in the 1972 Manufacturer’s Championship series, too many of whom are no longer with us, none of what I was able to do would have been possible. I was also very fortunate to have an extremely talented group of film makers working with me from the moment we hit the ground running at the start of the season. The extremely kind things people have said about the The Speed Merchants and the favorable reviews it has received over the past 23 years should be shared equally with them.

- rtl gp 1.tif

- rtl gp 2.tif

Comments are closed.